Turning antibody sequences into live-cell tools

I have a soft spot for methods that turn messy cell biology into something that is more quantifiable. When a tool works, it helps bring true progress into our understanding of fundamental biology. When it fails, you can lose weeks to cloning, expression quirks, or reagents that behave differently every time you thaw them.

This recent Science Advances paper tackles one of these frustrations by taking an antibody sequence and turning it into an intrabody, an antibody-derived binder that functions inside living cells.

Intrabodies: why?

Most antibodies evolved to work outside cells, in environments that help them fold correctly and maintain their disulfide bonds. The cytoplasm, however, is harsher, more crowded, and chemically different. Many antibody fragments misfold or aggregate there, which is why intracellular antibodies have historically been difficult to make reliable.

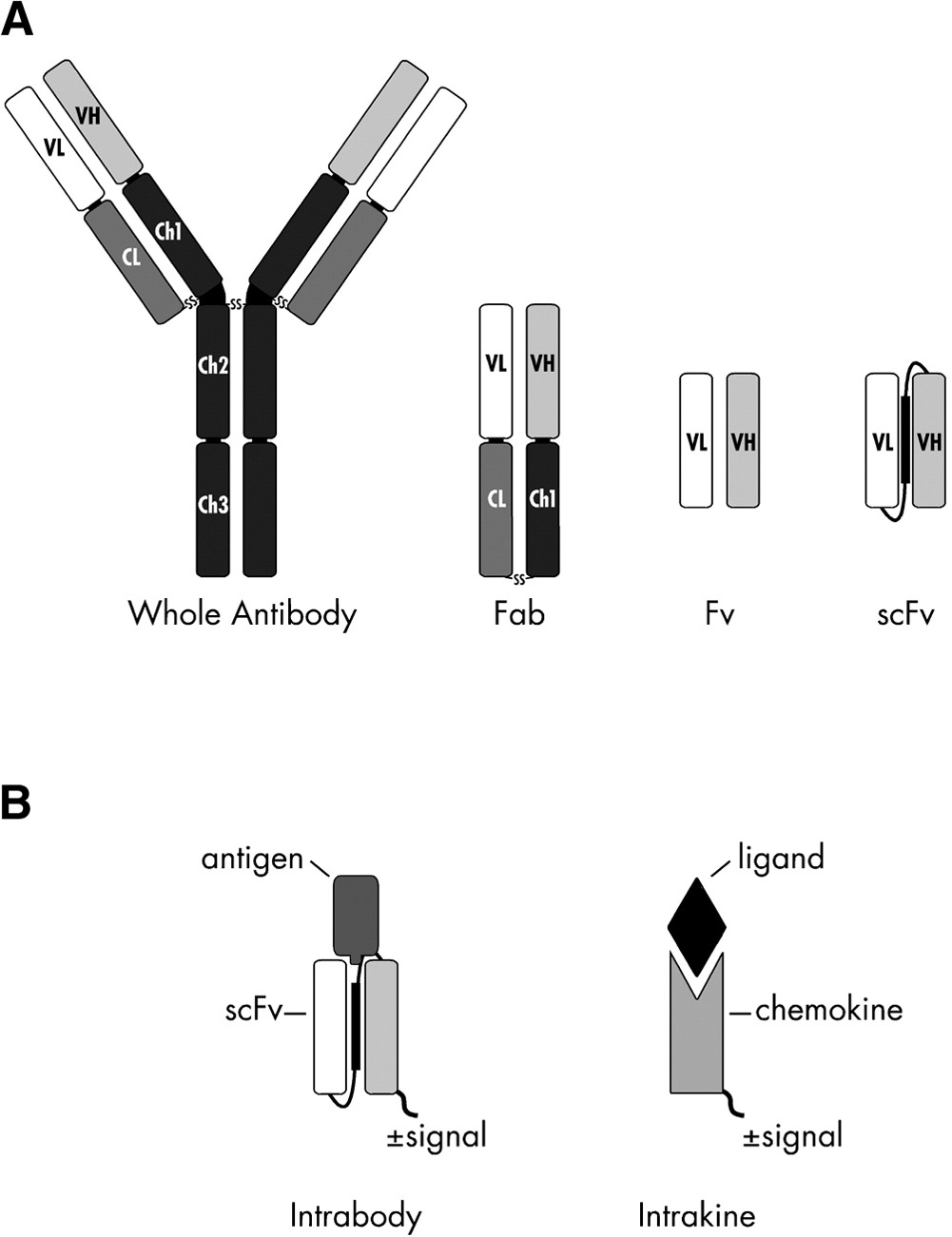

Intrabodies are antibody-derived binding proteins that are engineered to function inside living cells. Structurally, they are usually fragments of full antibodies, most often single-chain variable fragments (scFvs), where the heavy and light variable domains are linked into a single polypeptide. Functionally, the key difference is location: conventional antibodies act extracellularly or in secretory compartments, while intrabodies operate in the cytoplasm or nucleus.

If you can get them to work, the payoff is large. Intrabodies let you visualize targets that cannot be genetically tagged. Histone modifications are one of the big examples. You can fuse GFP to a histone protein, but you cannot directly label a acetyl or methyl group that appears and disappears on a histone tail. Intrabodies aimed at these epigenetic modifications make it possible to watch chromatin regulation unfold dynamically in living cells.

The authors of this new Science Advances paper describe a workflow that keeps the binding loops of an antibody fixed while re-engineering the surrounding framework to fold better inside cells. The pipeline combines antibody annotation, structure prediction, sequence redesign, and live-cell screening. They start with an antibody sequence, identify the binding loops, and use structure prediction plus ProteinMPNN-based redesign (a deep-learning based protein sequence design method) to modify mostly the framework so the same binder is more likely to fold and remain soluble inside cells. They then actually express candidates in living cells and screen for functional intrabodies (proper localization and target-dependent signal), iterating based on what actually works experimentally.

They first validate the approach on simple peptide targets, then apply it to a broader and more biologically interesting set: antibodies against multiple histone modifications, generating an expanded collection of so-called mintbodies for live-cell imaging.

The key result

Out of 26 starting antibody sequences, 19 were converted into functional intrabodies. Their selling point is that 18 of those 19 had failed using the group’s standard conversion method (although I always wonder how many they tried in total, and what happened to the ones that failed!). The redesigned variants from their pipeline show proper expression and localization in cells, and selected examples respond as expected when histone modification levels are experimentally perturbed.

If this approach generalizes, it lowers the barrier to turning antibody sequences into intracellular tools. That matters because antibody sequences are becoming easier to obtain and share, while reliable intracellular binders are hard to come by. A more systematic path from sequence to function could shift intrabodies to more regularly used tools. Even then, we still need experimental validation every time. The authors themselves point out that there is usually a trade-off between stability and function, where if you stabilize a product it can be too stable and no longer bind the intended target. While they try to sit in this Goldilocks zone, no computational tool is perfect.

One thing I'm missing here, is the relevant comparison to nanobodies: single-domain binders that are even more stable and cytosol-friendly than intrabodies. I assume the authors went for scFvs because of the larger library of data, especially in binding specific epitopes, allowing AI usage. But won't nanobodies cover much of the same ground, eventually? On top of this, how will this kind of pipeline hold up, when we're starting to see de novo protein binders in work shown by David Baker's lab and others? Only time will tell.