Other Minds

I read Other Minds by Peter Godfrey-Smith because it sits right at the intersection of my interests: sentience, evolutionary biology, and good popular science. I also think a lot about animal welfare. As a vegan, I care about where experience might show up across animals, and what the evidence can actually support. The book treats minds as biological phenomena shaped by evolution and environment, then uses cephalopods (octopuses, cuttlefish, and their relatives) as the main test case.

The book identifies two distinct roles for a nervous system that eventually contribute to consciousness. The first is the sensorimotor role, which is about an organism perceiving its environment and acting on it. This appears even in bacteria, which use chemical sensors to "perceive" nutrients and flagella to "act" by swimming toward them. Animals just scale this up using a nervous system. The second is the action-shaping role, which is the internal coordination of the body. In a multicellular animal, the nervous system has to organize a collection of individual cells into a single agent that moves in unison. Godfrey-Smith suggests that while many organisms sense and react to the world, the specific way an animal coordinates its own internal complexity is what begins to build a self. From there, questions about inner life feel tied to how an animal keeps itself going in a messy world in real time.

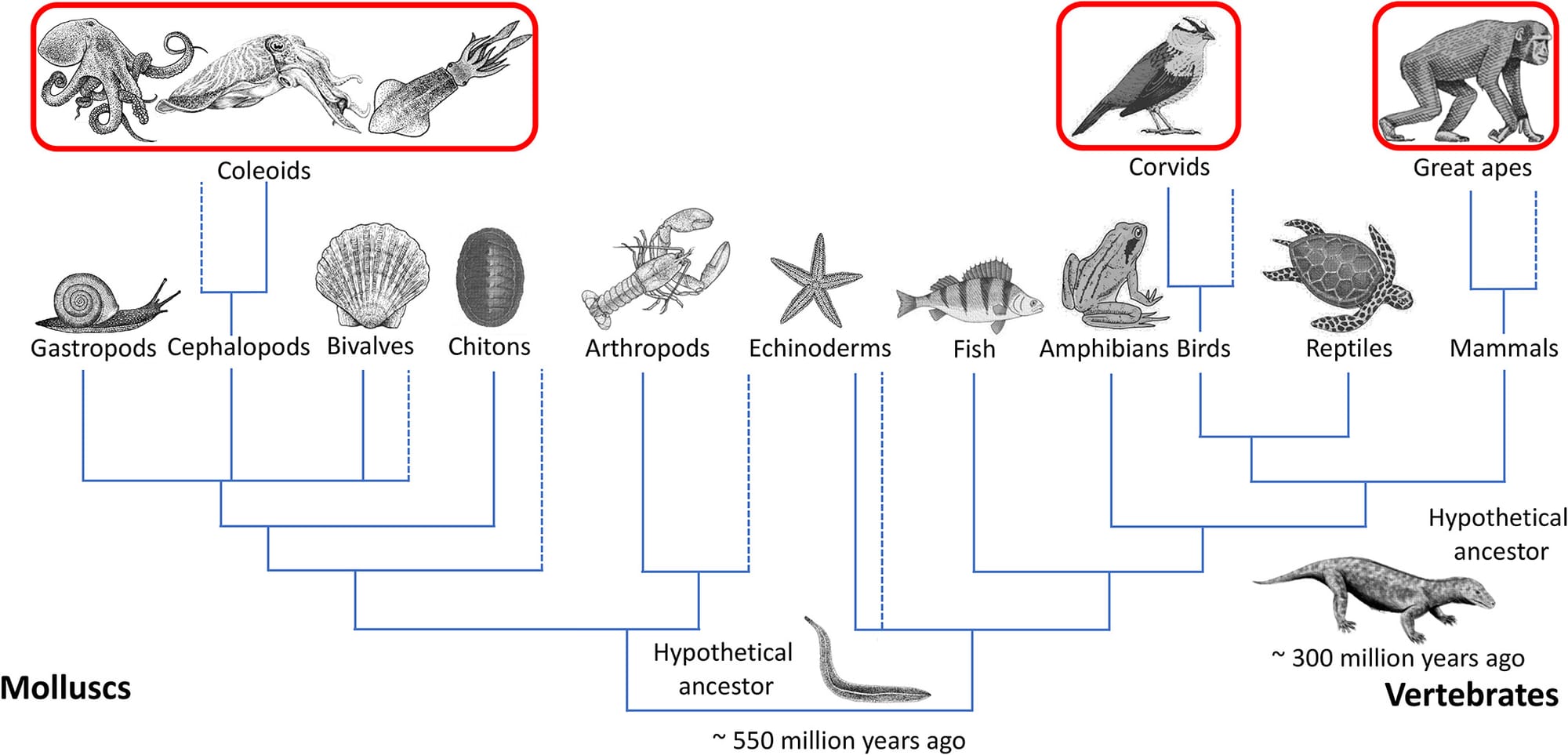

Cephalopod intelligence is the main thread throughout the book. Octopuses and their relatives evolved complex behavior on a branch far from vertebrates, which makes them an evolutionarily separate example of sophisticated cognition. I learned that the split between the branch that ended up leading to cephalopods and the branch leading to vertebrates was hundreds of millions of years ago. This was after neurons had already appeared in early animals, but well before either lineage developed large brains. Somehow evolution handed us a useful comparison in observing how different animal branches can develop complex neural connections leading to sentience, while finding two seemingly different solutions. When two distant lineages both end up at complex sentience, it raises a useful question: which parts are shared and which are different?

The most interesting difference between vertebrates and cephalopods, to me, is how distributed a cephalopod nervous system is. A large share of octopus neurons sit in the arms, often cited as about two-thirds, and they have a lot of local control over behavior. Even a freshly amputated arm can still produce coordinated grasping, withdrawal, and tightening responses when the suckers are touched or the arm is irritated, and those patterns can look organized rather than random.

Despite this, the central brain of the octopus still has a large degree of control. The brain seemingly can bias the arms' behavior and sometimes completely override local rules that are implemented peripherally (like the tendency of suckers to avoid strongly attaching to the animal’s own skin, which helps prevent self-tangling). In special mazes where the solution is to leave the maze by taking a detour that initially moves away from the obvious path, octopuses can still solve the problem, which suggests the system can combine high-level centrally driven strategy with very local, arm-driven exploration and execution.

Even though the animal is one organism, the control architecture is spread out across the body. In comparison, we feel like we are practically a single control unit that bosses around our entire body. What does it feel like to be an octopus, when your arms have their own control units that determine movement and how to respond to the environment? When your entire body is involved in decision making? Can we even imagine what this would be like?

Somewhat surprisingly, humans also have some degree of decentralization. Split-brain work is an example that our experienced unity may not be what it seems, and that by interrupting good flow of information between the hemispheres can expose this. As a refresher, in the classic setup a split-brain patient can name an object flashed to the right visual field, yet when the object is flashed to the left visual field they will say they saw nothing, while the left hand can still point to the matching object or draw what was seen. When asked why they picked it, they may confidently give an explanation that does not reflect the real driver of the choice. To me it sounds like we do have something in common with cephalopods.

The last topic in the book that I really liked is on aging and life history. While cephalopods are clearly sentient and intelligent, they have remarkably short lifespans of often one to five years! The book continues to discuss evolutionary investment, the costs of building and maintaining complex nervous tissue, and how selection pressures can still lead to very short lifespans. This bit was so interesting that I will probably come back and build a small simulation on this topic to explore it more.

Overall, I found it a good read with lots of interesting science. As a lab scientist, I was genuinely surprised by how much time Godfrey-Smith seems to spend in the water, watching, returning, and building familiarity with particular animals. The philosophical ideas come across even better due to the intermission of concrete descriptions of cephalopod behavior, behavior that can feel almost alien in its logic and body language. By keeping it real and describing the behavior in person it also becomes much easier to read the book.

On the ethical side, the book did not pull me toward ambiguity or caution in a narrowing sense. It pushed me outward. If minds are widespread and diverse, and do not have to look like ours, then the safer direction is to widen the circle of moral concern. My intuitions about sentience may be too small-minded right now. We do not fully understand our own consciousness, and we understand other nervous systems like the cephalopod's even less. Given the uncertainty, and given what is at stake for the animals themselves, I find it hard to justify quickly ruling out an animal species' sentience even when unfamiliar to us.