How do bacteria know which way the food is?

For E. coli, the trick is chemosensing: it swims in straight runs, occasionally tumbles around, and biases that run-tumble pattern so it slowly gets closer to a food source. It does this by trying to increase the amount of gradient it senses, ie. following the attractant gradient. There's a problem though: as a small bacterium (~1 μm), it cannot measure a spatial gradient across its body like we could, as it has too small of a change over its body. Instead, it measures concentration along time, as it moves through space. Based on at what time it measures high concentrations, it knows where to go. Sounds simple, but there's problems around the corner.

One of the problems in this plan is noise. Molecules have to stochastically arrive at receptors by diffusion. Even if the bacterium has a perfect interpretation of the signal, the receptor sees a noisy process. In 1977 (and a long line of follow-up work), Berg and Purcell argued that diffusion-driven arrival noise is a fundamental limit on how accurately a cell can estimate environment concentration and respond.

Very recently, we got a new update on this problem in Nature Physics. The authors want to test if the physical arrival noise is actually what limits E. coli chemotaxis in practice? In their framing, the relevant quantity is the rate of change of log concentration along the cell’s path,

Here \(c(t)\) is the concentration encountered by the cell, and \(s(t)\) is the target quantity the cell would like to estimate from its noisy observations.

There are two channels that carry the information about \(s(t)\):

1) The physical channel: the time series of arrivals at receptors, written as arrival rate \(r(t)\). This is the earliest observable variable, so it defines a physics-side upper-limit for what any downstream system could possibly infer about \(s(t)\).

2) The biological channel: the intracellular chemotaxis pathway activity downstream of the receptors, which the authors here link back to the receptor-associated CheA kinase activity \(a(t)\). This is closer to what the bacterium can actually use to control its motors.

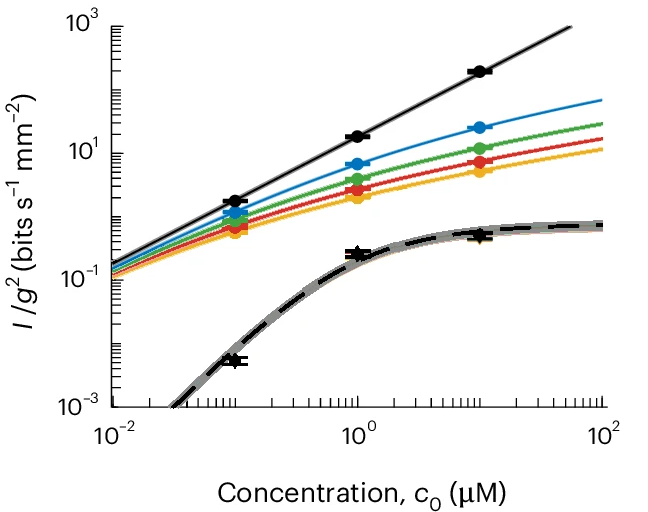

To figure out where the information actually is carried and how much of it ends up where, they build an information-theoretic estimator. This estimator contains both information about \(s(t)\) and the arrival process \(r(t)\), and they estimate how much information about \(s(t)\) is present in the measured kinase activity \(a(t)\).

Experimentally, the second part does single-cell measurements of pathway activity using FRET (plainly put: a way to figure out if molecules are interacting), across multiple background concentrations. From this they can figure out the response to dynamic concentrations, similar to what chemotaxis requires.

What did they find?

First, they found that typical E. coli encode about two orders of magnitude less information than the physical limit! In their summary: chemosensing is limited by internal noise in signal processing, rather than by molecule arrival noise.

As someone who thought about noise and chemical reactions in the past, it's easy to think about what noise does to chemistry and assume it stops there. Yet here, the main limitation shows up after the receptors, in cellular signal-processing chains. They support this finding further with simulations, showing that the cell's gradient climbing is far below what the physical arrival noise alone would allow.

The main takeaway I had from this paper is that we often focus on physical limits when we're initially drawing boundaries. When we examine closer, we often find that biological solutions to problems have more limitations and are often well within physical limits. Maybe we should start incorporating this in our napkin math.