Evolutionary origins of aging

If you ask why we age, you can easily end up in the weeds of mitochondria, telomeres, senescent cells, cancer suppression, and a dozen other mechanisms that sound like the culprit. Biology offers many proximate causes of decline, and it is tempting to treat them as competing explanations. The risk is that you end up with a very detailed story about how bodies fall apart, while the deeper question stays unanswered: why does evolution so often tolerate bodies that fall apart at all.

I hinted at this in my Other Minds review, because the author talks about this with regards to why cephalopod lifespans are so short. You can have an animal with sophisticated behavior, and yet a life that often ends after a few short years. Why would you make a complex body if it doesn't get to use its complexity to reach a certain payoff? On the other hand, we have plenty of examples of animals that live long lives, such as humans, which seems to make sense for us. Longevity is not granted, and evolution weighs out its benefits.

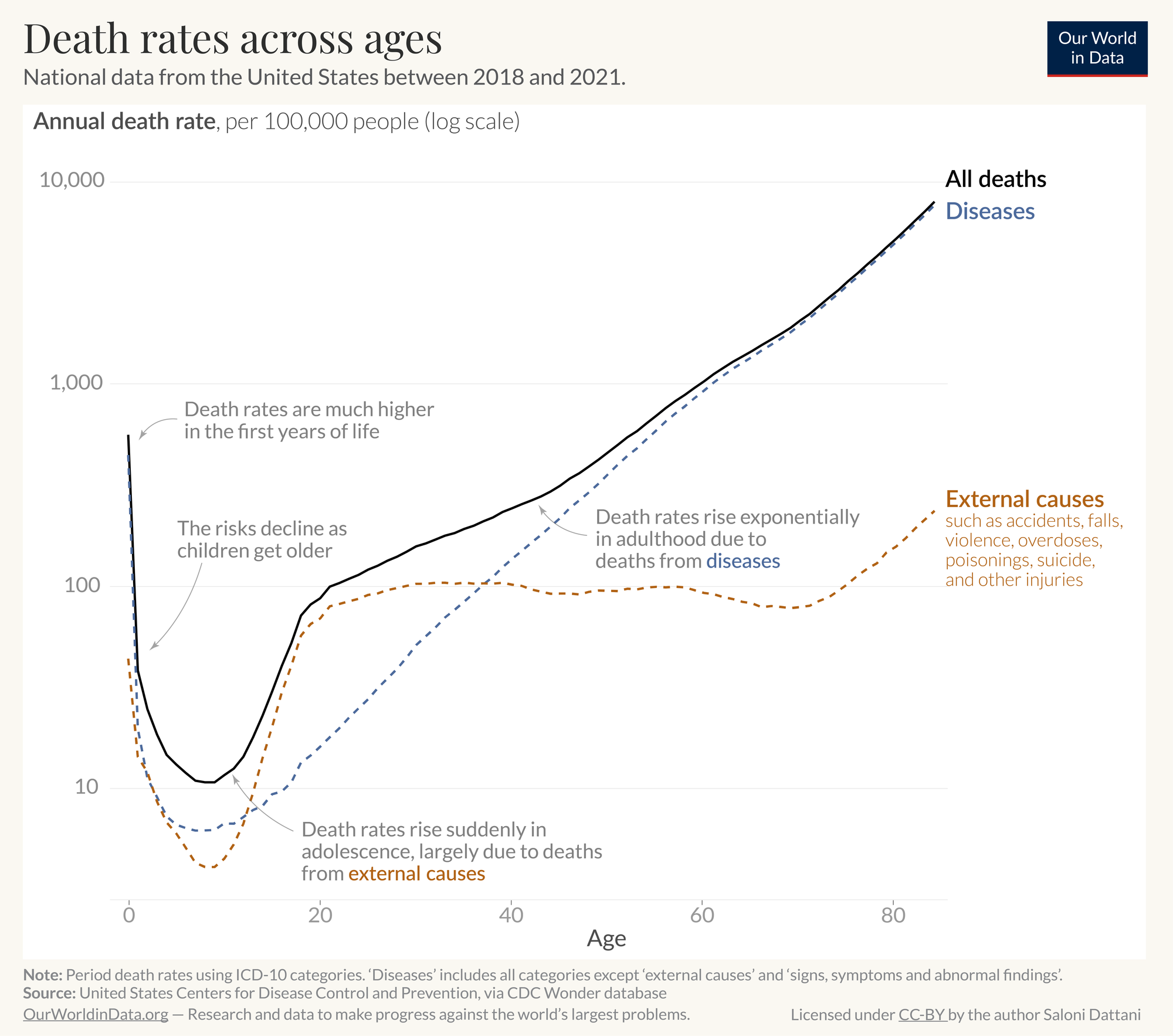

There is a clean empirical pattern that makes a good target for a toy explanation. If you look at age-related death rate across the human lifespan, the adult portion rises roughly exponentially with age, meaning it becomes close to a straight line when you plot it on a log scale (see the Our World In Data graph below). That pattern is surprisingly stable across places and periods once you get past early life and adolescence, even though the overall level shifts with public health and safety. The question I will look at in this post is how you can get that adult shape from evolutionary logic. You may be tempted to think that our chance of dying just increases as we get older due to failing biology, but that is begging the question. I'm interested in figuring out why evolution found the solution of allowing failing biology, and how this is a good strategy.

The key evolutionary intuition is that late life is priced differently from early life. Selection pushes hard on traits that improve early survival and reproduction, then its leverage weakens as the remaining opportunity to produce descendants runs out. Several classic frameworks sit under this umbrella. Firstly, mutation accumulation argues that late-acting harmful effects are harder to purge because selection is weaker at late ages. Secondly, antagonistic pleiotropy argues that variants that boost early fitness can still be favored even when they carry delayed costs that show up later.

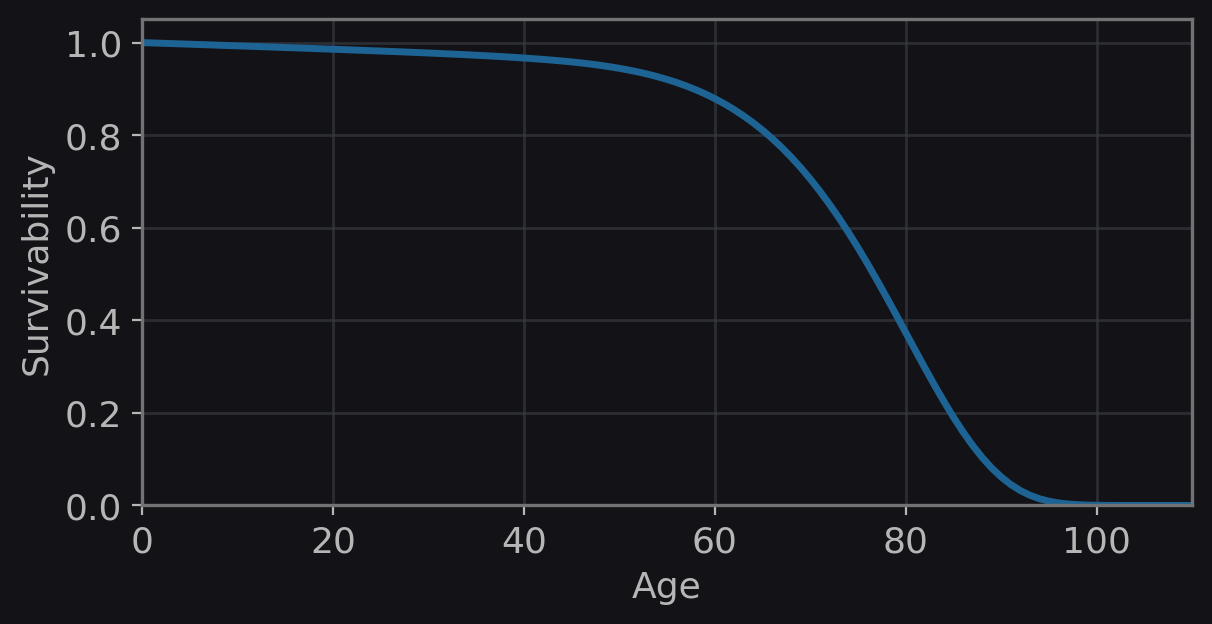

Instead of jumping straight into equations, I built a small interactive toy model that makes the ideas visible. It has a few examples, including a human-like curve, a bird-like curve, a cephalopod-like curve, and a long-lived reptile-like curve. Each preset shows the panels survivorship, hazard, a curve that tracks how quickly future reproductive value decreases, accumulated damage, and cohort deaths. The point is to see how changing simple parameters can shift how long an individual lasts.

Advanced

For readers who want the inner workings of the simulation, the rest of the post lays out the minimal math that generates those curves.

What pushes lifespans down and what pushes them up

An evolutionary explanation of aging gets clearer once you keep the cost and rewards of aging separate. Costs push lifespans down by making late survival a poor deal in reproductive terms. Rewards push lifespans up by rewarding maintenance when it increases future descendants.

The downward pressure is easy: selection cares about survival at an age only up to when being alive at that age can increase the number of descendants. As future reproduction runs out, the leverage of selection on late survival weakens. This line of thinking runs through Medawar, and it was formalized as an age-dependent weakening of selection by Hamilton. One consequence is mutation accumulation: harmful effects that arrive after the ages that matter can be harder to purge.

A closely related idea is antagonistic pleiotropy. Some genetic variants can improve early-life fitness components, like growth, fertility, or early survival, while also having harmful effects later. Even if the late costs are real, selection can still favor the variant because the early benefits are paid out when selection is strongest. Williams first came up with this tradeoff , and it explains why aging can emerge without any single late-life mechanism being the whole story.

The upward pressure is also relatively simple: survival and function are evolutionarily valuable when they protect reproduction, and they can remain valuable when later life still feeds back into descendants through any means such as transfer of knowledge or protection. Humans are a good example of this, since we take a relatively long time to reach maturity compared to other species and depend a lot on our parents until then.

To make the selection shadow visible in a model, it helps to quantify how much future payoff remains at each age. The next few definitions build a simple proxy for that remaining value from a fertility schedule.

One way to make the selection shadow concrete is to write a reproductive value proxy from a fertility schedule. Let \(g(a)\) be the reproductive output at age \(a\). In a toy model, \(g(a)\) can be a flat window: approximately zero before maturity, roughly constant during reproductive ages, then dropping after reproduction ends.

The remaining expected reproductive output from age \(a\) onward is then:

We then scale this function so it starts at 1 and decreases over time, defined as \(w(a)\).

The function \(w(a)\) tunes how much future payoff there is for survival. Early in life it sits near one, because survival still protects a large share of future reproduction. Later it comes down toward zero as the remaining opportunity to turn survival into descendants disappears. When \(w(a)\) is small, late problems are selected against more weakly, which is the intuitive reason mutation accumulation becomes plausible.

The upward forces enter through maintenance. If keeping the individual's biology in better shape increases future descendants, selection has a reason to pay the cost for repair. Of course, maintenance isn't free. A common evolutionary framing is that organisms face a tradeoff between investment in reproduction and investment in somatic maintenance, with aging emerging from imperfect maintenance over time.

A useful simplification is to treat maintenance investment \(m\) as both slowing damage accumulation and reducing effective fertility through a cost parameter \(c\), as described by Kirkwood. The effective reproductive output now depends on the baseline fertility schedule \(g_0(a)\), the maintenance investment \(m\), and the cost \(c\).

This is the point where proximate biology starts to come into the picture. Telomeres, mitochondria, proteostasis, senescent cells, and tumor suppression are candidates for how maintenance is implemented, and for where it can stop being worth paying the cost.

A minimal model that produces adult acceleration

We can see that in adult humans mortality hazards rise close to exponentially across a broad adult age range (see the OWID graph again), which appears approximately linear on a log-hazard plot. I tried to get this effect by making the accumulated damage make the hazard risk grow exponentially, which intuitively matches some biological ideas such as DNA damage.

The model tracks a hidden damage load \(D(a)\) and maps it to an annual hazard of death \(\mu(a)\). Mortality has an age-independent component \(\mu_{\mathrm{ext}}\) and an age-dependent component, which is the hidden damage load. Here \(\mu_{\mathrm{ext}}\) represents extrinsic or background risk, often interpreted as external causes such as accidents and acute infections, while \(\alpha\) converts internal damage into risk. The difference in extrinsic hazard is another difference between species and can thereby also lead to different natural lifespans. Hazard is now defined as:

Using the hazard, we can figure out survivorship \(\ell(a)\).

Age dependence is also incorporated in \(D(a)\). Damage has baseline wear \(d_0\), plus a late-acting component that becomes more influential once the selection pressure lowers.

A compact expression for the mutation-accumulation increment is:

The parameter \(u\) sets how much extra damage per year can occur. The parameter \(p\) controls how sharply the effect turns on as the selection shadow deepens. The onset profile \(\nu(a)\) determines when the damage begins to appear, and in the embedded tool it is implemented as a bell-shaped curve for simplicity. The term \((1-w(a))^{p}\) acts as a filter: when \(w(a)\) is high, the filter is mostly closed and late-acting harm contributes little; as \(w(a)\) drops, the filter opens and more of the late-acting contribution gets through.

A purely additive damage model often produces a hazard that rises too gently to resemble adult demographic patterns. As I mentioned, I solved this by making the damage compounding, where deficits increase vulnerability to future deficits.

The model represents compounding in the following way:

The annual increment \(\Delta D(a)\) combines baseline wear and the late-acting term, slowed by maintenance investment \(m\) with efficiency \(k\):

In the toy model, the selection shadow determines when late-acting harm becomes cheap enough for evolution to tolerate, and the feedback term \(\gamma\) determines what happens once that harm is present. When \(\gamma\) is near zero, damage mostly accumulates as a slow drift. When \(\gamma\) is positive, existing damage amplifies future damage, so risk accelerates in a way that can look close to exponential across adulthood. That is the bridge back to biology: organisms are coupled systems, and once repair and buffering are no longer strongly favored by selection, small deficits can propagate through the rest of the machine.